UX lessons for EU grants

Writing a funding application should be no different than any other piece of persuasive writing. It needs to be thought through bearing the user experience in mind.

All too often, reading a project proposal is boring. They tend to be long winded, repetitive and with poor use of language. All in all, the user experience is bad.

Unfortunately, in this case, the users are the evaluators who decide on who will receive the funds.

Even though you seem constrained by the European Commission’s templates – seldom user friendly – you should approach drafting a project for EU funding like any other business proposal. That is what it is in the end: a description of a product or service you are requesting funding for.

Focus on the user’s needs

Google has a rule that applies to this situation: “focus on the user and all else will follow”. The tech giant considers that any product design needs to “take great care to ensure that they will ultimately serve [the user], rather than our own internal goal or bottom line.”

In this case the evaluator is the user and their decision will affect your organisation’s bottom line.

Project evaluators will go through piles of proposals at each call the Commission publishes. Although their objective is to determine the quality of the proposed actions, technology or research, the wording will, inevitably, influence their decision.

When writing a project proposal, you should take the evaluator - user of your document - into account. They are generally external to Commission staff and may not know all EU concepts, legislation or acronyms off the top of their heads. Moreover, as English may not be their native language, complicated writing will make for a complicated read.

Most importantly, they are tired of reading long, technical project proposals all on the same subject. Why will yours stand out to them?

Poorly written proposals will distract from the content and will make you lose points which could cost you your grant.

Not a native? Not an excuse!

The EU has 24 official languages, but most calls for proposals must be submitted in English. Evaluators will only see the added value of your proposal if it is written in excellent English. This may seem unfair but bear in mind that being a native speaker of a language does not necessarily make one a good writer or communicator.

Confused writing is an indication of confused thinking. In a competitive environment like that of EU grants, no one will consider proposals that read like they were written by someone who has lost the plot.

Create a clear flow

Do not jump straight into the Commission’s template and start writing because they do not always make good writing companions. Lay out the essence of your project proposal first, ensure it is coherent and explains what you are going to bring to the table.

Design a flow chart or diagram indicating how the various activities connect and relate to one another. A project flowchart is its UX flow, it lays out the path a user will follow through your project and helps immerse them in what they are reading. It will help get the evaluator “in the zone”.

If you find it difficult to draw a comprehensible chart, it may well be that your project is poorly structured. If you find it difficult to follow your own logic, what can you expect of the evaluators?

Then proofread your lay-out! It is tempting, once you have your outline to go straight to filling in the proposal. You justify any odd wording by saying you will proofread the entire proposal when it is finished. But if something is unclear or confused, the more you write around it, the more you will lose your thread and muddle the issue.

Engage the evaluators

Your proposal should be written clearly, using short sentences and an active voice. Explain what is going on, what will - or will need to - be done and by whom. Do not use passive language or vague concepts.

In 2015, the City of Boston considered making a bid for the Summer Olympic Games of 2024. The Boston Foundation contracted the Donahue Institute of the University of Massachusetts to assess the economic implications of a bid.

The document – “Assessing the Olympics, preliminary economic analysis of a Boston 2024 Games – impacts, opportunities and risks” – was poorly written. The City of Boston never submitted their bid.

Business strategist Josh Bernoff writing in the Harvard Business Review highlights how the passive voice of the report made relatively straight forward economic issues - that all major endeavours face, including your project – seem insurmountable.

The passivity of the text hid the basics: who is responsible for this part of the project?

He points to sentences like: [These] are issues that will need to be closely monitored in order to ensure the public sector is protected from extensive financial commitments. To date, using insurance to protect a host city from cost overruns has not been used extensively.

The Olympic bid became mired in questions over who was in charge of monitoring expenses or obscure insurance matters. This cast a shadow over the public debate and in the end both citizens and city officials agreed to pull the bid.

Your proposal may not be a big thing like the Olympics, nevertheless, active language has two advantages: it forces writers to be specific and to find coherent and clear arguments to support their case; and it makes clever people stand out.

In 2016, Bernoff surveyed around 550 US business people whose jobs require at least two hours of writing a week excluding emails. 81% of respondents agreed that poorly written material wastes a lot of their time. It was seen as ineffective because of its length, poor organisation, excessive use of jargon and lack of precision.

In-house jargon is not appropriate

Use plain English when you write your project proposal. When writing a research project or a highly technical project, technical terms in the right places are fine, but the text as a whole should be as jargon free as possible. Do not forget to spell out acronyms the first time you introduce them in your text.

EU project evaluators might be familiar with Commission jargon, acronyms and Eurospeak generally. However, like any reader (or user), they will also be distracted or become confused by a piece of writing that is excessively and unnecessarily jargon charged.

The European Commission updated this January its English Style Guide. The main targets of this handbook are “authors and translators” in the institution, but it is worth checking out.

Right out of the gates - on page 4 – the guide highlights that legal and bureaucratic language is necessary in legislative texts, with Eurospeak being an acceptable shorthand between Commission departments, but where documents address a broader public “in-house jargon is not appropriate”. A sentiment that echoes Kingsman Brewster Jr, former President of Yale University who once stated: “Incomprehensible jargon is the hallmark of a profession”.

According to the Commission’s guide, documents must be “immediately understandable” even to those unfamiliar with the workings and the vocabulary of the EU. In Commission terms, this is the “could I explain it to my grandmother?” maxim, and it applies to project proposals.

The guide goes on to suggest that documents should use “short paragraphs”, “simple syntax”, and “highlighting devices such as bullets”. Sound familiar?

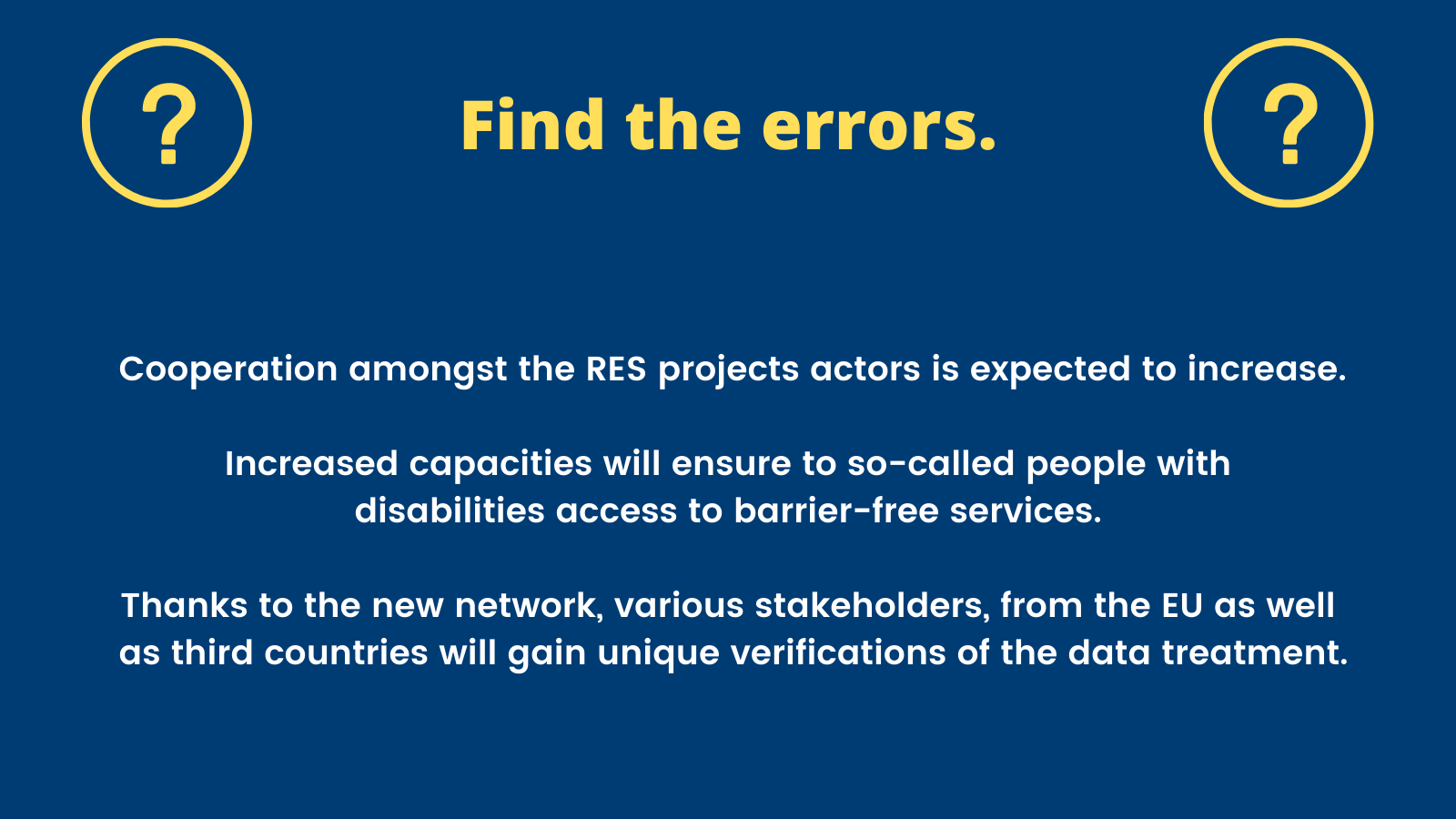

Grammar matters

After weeks during which you and your colleagues have spent countless hours working on your project proposal, you only have energy left to upload it onto the Commission’s portal. However, you should review and proof it.

Make sure that the activities and work packages flow correctly. Consider whether all the activities in the project are necessary, some may be superfluous. Ensure that the same active tone is used throughout and that the language is clear and easy to read: grammar matters!

Generally a project proposal has been worked on by several people, using different styles, vocabulary and, perhaps their own understanding of the project flow. A fresh pair of eyes should go over the entire document, testing the connection between activities. Make sure the UX flow is not broken.

If everyone in your team has project proposal-fatigue, and there are no fresh eyes left in the room, send it to us or any other external, experienced proofreader. This should not be chalked up as an extra cost or loss, but an investment that will help your organisation make a return.

Three UX tips to write better grant applications

Focus more on the funders’ needs than internal goals.

Lay out the project’s flow before filling out the official template.

Keep it consistent and have someone external to the project writing team check the document before submission.

- written by Benjamin Wilhelm, benjamin[at]thedandeliongroup.eu

Learn the techniques. Boost your confidence. Make your point.

Click here to unlock potentials.